Newsletter – November 2019

NEWS

Welcome to the November edition of this newsletter.

True to form, the Practical Workshop was blessed with clear skies. Despite the low attendance, we all set up equipment and made the most of the dark sky until the moon made an appearance later in the evening. Derek Myatt even managed to observe Uranus for the first time using his portable setup.

Despite the horrendous weather during the day, Stargazing in Audley was a success. the skies cleared just as we arrived to set up and lots of people turned up to get a view of the night sky through the variety of telescopes set up outside.

Inside, the video presentation kept the adults occupied while the children engaged in the craft table.

Overall, a good turnout considering the weather and lots of people asking when the next one is…..

I’m looking forward to this month’s presentation by Robert Ince. It’s entitled “Turning astro-photos into science” by Robert Ince. (NSAS Members £3.00 – Non Members £5.00). Further details are here.

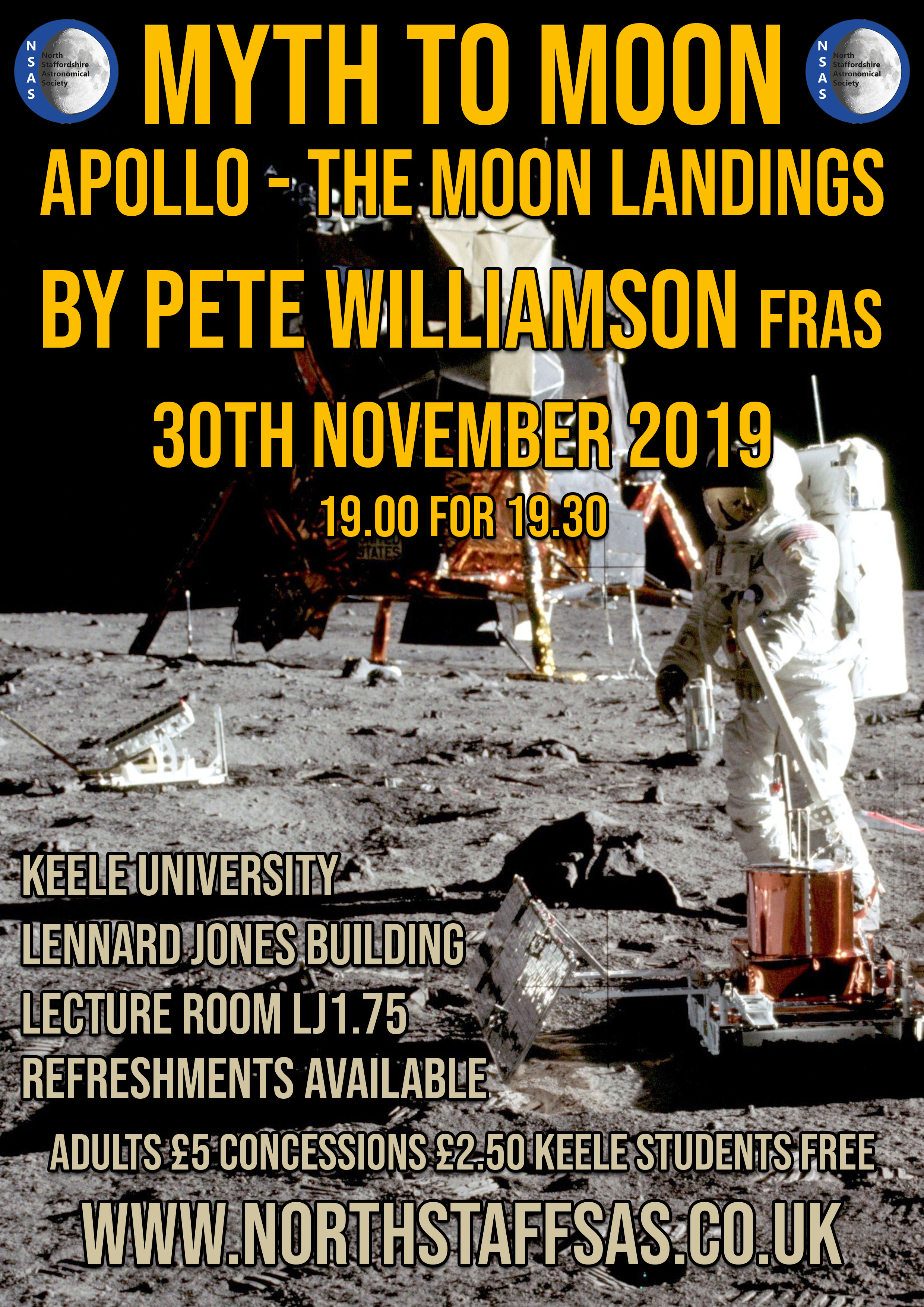

Also coming up at the end of the month is our headline talk from Pete Williamson entitled “Myth to Moon”, this will be held at Keele University, details on the website

This month’s observing night will be on 23rd November weather permitting.

The next practical workshop is scheduled for Wednesday 20th November. This and any other events are listed on the NSAS Events page.

May I remind everyone that the society solar scope is available throughout the winter too! It is on a monthly basis and there is just a £25 returnable deposit required. Contact me at the email below or see me at the meeting. More details here.

If anyone has any ideas for new features on the website or on any improvements you’d like to see to existing ones then please drop me an email or text.

Also keep an eye on our Facebook page as any breaking news will more than likely appear there first as I can update that from my phone.

Our new members Facebook group is here

The sky maps can be downloaded from here

The next regular meeting is on December 3rd, which is Gary Palmer – Equipment Guide for Beginners

If anyone has anything they want to include on the website/newsletter/etc then please email me secretary@northstaffsas.co.uk

Wishing you clear skies, Duncan

SKYMAP

|

Sky Calendar — November 2019

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CONSTELLATION OF THE MONTH

-

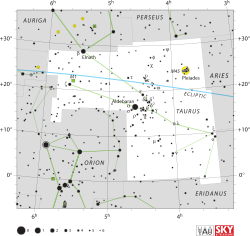

Taurus (constellation)

Jump to navigationJump to search

Taurus Constellation Abbreviation Tau[1][2] Genitive Tauri[1] Pronunciation Symbolism the Bull[1] Right ascension 4.9h[4] Declination 19°[4] Quadrant NQ1 Area 797 sq. deg. (17th) Main stars 19 Bayer/Flamsteed

stars132 Stars with planets 9 candidates[a] Stars brighter than 3.00m 4 Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) 1[b] Brightest star Aldebaran (α Tau) (0.85m) Messier objects 2 Meteor showers Bordering

constellationsVisible at latitudes between +90° and −65°.

Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of January.Taurus (Latin for “the Bull“) is one of the constellations of the zodiac, which means it is crossed by the plane of the ecliptic. Taurus is a large and prominent constellation in the northern hemisphere‘s winter sky. It is one of the oldest constellations, dating back to at least the Early Bronze Age when it marked the location of the Sun during the spring equinox. Its importance to the agricultural calendar influenced various bull figures in the mythologies of Ancient Sumer, Akkad, Assyria, Babylon, Egypt, Greece, and Rome.

A number of features exist that are of interest to astronomers. Taurus hosts two of the nearest open clusters to Earth, the Pleiades and the Hyades, both of which are visible to the naked eye. At first magnitude, the red giant Aldebaran is the brightest star in the constellation. In the northwest part of Taurus is the supernova remnant Messier 1, more commonly known as the Crab Nebula. One of the closest regions of active star formation, the Taurus-Auriga complex, crosses into the northern part of the constellation. The variable star T Tauri is the prototype of a class of pre-main-sequence stars.

Contents

Characteristics[edit]

Taurus is a large and prominent constellation in the northern hemisphere‘s winter sky, between Aries to the west and Gemini to the east; to the north lies Perseus and Auriga, to the southeast Orion, to the south Eridanus, and to the southwest Cetus. In late November-early December, Taurus reaches opposition (furthest point from the Sun) and is visible the entire night. By late March, it is setting at sunset and completely disappears behind the Sun’s glare from May to July.[5]

This constellation forms part of the zodiac and hence is intersected by the ecliptic. This circle across the celestial sphere forms the apparent path of the Sun as the Earth completes its annual orbit. As the orbital plane of the Moon and the planets lie near the ecliptic, they can usually be found in the constellation Taurus during some part of each year.[5] The galactic plane of the Milky Way intersects the northeast corner of the constellation and the galactic anticenter is located near the border between Taurus and Auriga. Taurus is the only constellation crossed by all three of the galactic equator, celestial equator, and ecliptic. A ring-like galactic structure known as Gould’s Belt passes through the constellation.[6]

The recommended three-letter abbreviation for the constellation, as adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1922, is “Tau”.[2] The official constellation boundaries, as set by Eugène Delporte in 1930, are defined by a polygon of 26 segments. In the equatorial coordinate system, the right ascension coordinates of these borders lie between 03h 23.4m and 05h 53.3m, while the declination coordinates are between 31.10° and −1.35°.[7] Because a small part of the constellation lies to the south of the celestial equator, this can not be a completely circumpolar constellation at any latitude.[8]

Features[edit]

The constellation Taurus as it can be seen by the naked eye.[9] The constellation lines have been added for clarity.

During November, the Taurid meteor shower appears to radiate from the general direction of this constellation. The Beta Taurid meteor shower occurs during the months of June and July in the daytime, and is normally observed using radio techniques.[10] Between 18 and 29 October, both the Northern Taurids and the Southern Taurids are active; though the latter stream is stronger.[11] However, between November 1 and 10, the two streams equalize.[12]

The brightest member of this constellation is Aldebaran, an orange-hued, spectral class K5 III giant star.[13] Its name derives from الدبران al-dabarān, Arabic for “the follower”, probably from the fact that it follows the Pleiades during the nightly motion of the celestial sphere across the sky.[14][15][16] Forming the profile of a Bull’s face is a V or K-shaped asterism of stars. This outline is created by prominent members of the Hyades,[17] the nearest distinct open star cluster after the Ursa Major Moving Group.[18] In this profile, Aldebaran forms the bull’s bloodshot eye, which has been described as “glaring menacingly at the hunter Orion”,[19] a constellation that lies just to the southwest. The Hyades span about 5° of the sky, so that they can only be viewed in their entirety with binoculars or the unaided eye.[20] It includes a naked eye double star, Theta Tauri (the proper name of Theta2 Tauri is Chakumuy)[21], with a separation of 5.6 arcminutes.[22]

In the northeastern quadrant of the Taurus constellation lie the Pleiades (M45), one of the best known open clusters, easily visible to the naked eye. The seven most prominent stars in this cluster are at least visual magnitude six, and so the cluster is also named the “Seven Sisters”. However, many more stars are visible with even a modest telescope.[23] Astronomers estimate that the cluster has approximately 500-1,000 stars, all of which are around 100 million years old. However, they vary considerably in type. The Pleiades themselves are represented by large, bright stars; also many small brown dwarfs and white dwarfs exist. The cluster is estimated to dissipate in another 250 million years.[24] The Pleiades cluster is classified as a Shapley class c and Trumpler class I 3 r n cluster, indicating that it is irregularly shaped and loose, though concentrated at its center and detached from the star-field.[25]

Deep-sky objects[edit]

In the northern part of the constellation to the northwest of the Pleiades lies the Crystal Ball Nebula, known by its catalogue designation of NGC 1514. This planetary nebula is of historical interest following its discovery by German-born English astronomer William Herschel in 1790. Prior to that time, astronomers had assumed that nebulae were simply unresolved groups of stars. However, Herschel could clearly resolve a star at the center of the nebula that was surrounded by a nebulous cloud of some type. In 1864, English astronomer William Huggins used the spectrum of this nebula to deduce that the nebula is a luminous gas, rather than stars.[26]

To the west, the two horns of the bull are formed by Beta (β) Tauri and Zeta (ζ) Tauri; two star systems that are separated by 8°. Beta is a white, spectral class B7 III giant star known as El Nath, which comes from the Arabic phrase “the butting”, as in butting by the horns of the bull.[27] At magnitude 1.65, it is the second brightest star in the constellation, and shares the border with the neighboring constellation of Auriga. As a result, it also bears the designation Gamma Aurigae. Zeta Tauri (the proper name is Tianguan[21]) is an eclipsing binary star that completes an orbit every 133 days.[13]

Brightest NGC objects in Taurus[28] Identifier Mag. Object type NGC 1514 10.9 planetary nebula NGC 1647 6.4 open cluster NGC 1746 6 asterism[29] NGC 1817 7.7 open cluster NGC 1952 8.4 supernova remnant (M1) A degree to the northwest of ζ Tauri is the Crab Nebula (M1), a supernova remnant. This expanding nebula was created by a Type II supernova explosion, which was seen from Earth on July 4, 1054. It was bright enough to be observed during the day and is mentioned in Chinese historical texts. At its peak, the supernova reached magnitude −4, but the nebula is currently magnitude 8.4 and requires a telescope to observe.[30][31] North American peoples also observed the supernova, as evidenced from a painting on a New Mexican canyon and various pieces of pottery that depict the event. However, the remnant itself was not discovered until 1731, when John Bevis found it.[24]

The star Lambda (λ) Tauri is an eclipsing binary star. This system consists of a spectral class B3 star being orbited by a less massive class A4 star. The plane of their orbit lies almost along the line of sight to the Earth. Every 3.953 days the system temporarily decreases in brightness by 1.1 magnitudes as the brighter star is partially eclipsed by the dimmer companion. The two stars are separated by only 0.1 astronomical units, so their shapes are modified by mutual tidal interaction. This results in a variation of their net magnitude throughout each orbit.[32]

Central area of constellation Taurus, showing Aldebaran at the lower left.

Located about 1.8° west of Epsilon (ε) Tauri is T Tauri, the prototype of a class of variable stars called T Tauri stars. This star undergoes erratic changes in luminosity, varying between magnitude 9 to 13 over a period of weeks or months.[5] This is a newly formed stellar object that is just emerging from its envelope of gas and dust, but has not yet become a main sequence star.[33] The surrounding reflection nebula NGC 1555 is illuminated by T Tauri, and thus is also variable in luminosity.[34] To the north lies Kappa Tauri, a visual double star consisting of two A7-type components. The pair have a separation of just 5.6 arc minutes, making them a challenge to split with the naked eye.[35]

IRAS 05437+2502, a nebula

This constellation includes part of the Taurus-Auriga complex, or Taurus dark clouds, a star-forming region containing sparse, filamentary clouds of gas and dust. This spans a diameter of 98 light-years (30 parsecs) and contains 35,000 solar masses of material, which is both larger and less massive than the Orion Nebula.[36] At a distance of 490 light-years (150 parsecs), this is one of the nearest active star forming regions.[37] Located in this region, about 10° to the northeast of Aldebaran, is an asterism NGC 1746 spanning a width of 45 arcminutes.[29]

History and mythology[edit]

Taurus as depicted in the astronomical treatise Book of Fixed Stars by the Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi, c. 964.Taurus as depicted in Urania’s Mirror, a set of constellation cards published in London c.1825.The identification of the constellation of Taurus with a bull is very old, certainly dating to the Chalcolithic, and perhaps even to the Upper Paleolithic. Michael Rappenglück of the University of Munich believes that Taurus is represented in a cave painting at the Hall of the Bulls in the caves at Lascaux (dated to roughly 15,000 BC), which he believes is accompanied by a depiction of the Pleiades.[38][39] The name “seven sisters” has been used for the Pleiades in the languages of many cultures, including indigenous groups of Australia, North America and Siberia. This suggests that the name may have a common ancient origin.[40]

Taurus marked the point of vernal (spring) equinox in the Chalcolithic and the Early Bronze Age, from about 4000 BC to 1700 BC, after which it moved into the neighboring constellation Aries.[41] The Pleiades were closest to the Sun at vernal equinox around the 23rd century BC. In Babylonian astronomy, the constellation was listed in the MUL.APIN as GU4.AN.NA, “The Bull of Heaven“.[42] As this constellation marked the vernal equinox, it was also the first constellation in the Babylonian zodiac and they described it as “The Bull in Front”.[43] The Akkadian name was Alu.[44]

In the Old Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh, the goddess Ishtar sends Taurus, the Bull of Heaven, to kill Gilgamesh for spurning her advances.[45] Enkidu tears off the bull’s hind part and hurls the quarters into the sky where they become the stars we know as Ursa Major and Ursa Minor. Some locate Gilgamesh as the neighboring constellation of Orion, facing Taurus as if in combat,[46] while others identify him with the sun whose rising on the equinox vanquishes the constellation. In early Mesopotamian art, the Bull of Heaven was closely associated with Inanna, the Sumerian goddess of sexual love, fertility, and warfare. One of the oldest depictions shows the bull standing before the goddess’ standard; since it has 3 stars depicted on its back (the cuneiform sign for “star-constellation”), there is good reason to regard this as the constellation later known as Taurus.[44]

The same iconic representation of the Heavenly Bull was depicted in the Dendera zodiac, an Egyptian bas-relief carving in a ceiling that depicted the celestial hemisphere using a planisphere. In these ancient cultures, the orientation of the horns was portrayed as upward or backward. This differed from the later Greek depiction where the horns pointed forward.[47] To the Egyptians, the constellation Taurus was a sacred bull that was associated with the renewal of life in spring. When the spring equinox entered Taurus, the constellation would become covered by the Sun in the western sky as spring began. This “sacrifice” led to the renewal of the land.[48] To the early Hebrews, Taurus was the first constellation in their zodiac and consequently it was represented by the first letter in their alphabet, Aleph.[49]

In 1990, due to the precession of the equinoxes, the position of the Sun on the first day of summer (June 21) crossed the IAU boundary of Gemini into Taurus.[citation needed] The Sun will slowly move through Taurus at a rate of 1° east every 72 years until approximately 2600 AD, at which point it will be in Aries on the first day of summer.[citation needed]

In Greek mythology, Taurus was identified with Zeus, who assumed the form of a magnificent white bull to abduct Europa, a legendary Phoenician princess. In illustrations of Greek mythology, only the front portion of this constellation is depicted; this was sometimes explained as Taurus being partly submerged as he carried Europa out to sea. A second Greek myth portrays Taurus as Io, a mistress of Zeus. To hide his lover from his wife Hera, Zeus changed Io into the form of a heifer.[50] Greek mythographer Acusilaus marks the bull Taurus as the same that formed the myth of the Cretan Bull, one of The Twelve Labors of Heracles.[51]

Taurus became an important object of worship among the Druids. Their Tauric religious festival was held while the Sun passed through the constellation.[41] Among the arctic people known as the Inuit, the constellation is called Sakiattiat and the Hyades is Nanurjuk, with the latter representing the spirit of the polar bear. Aldebaran represents the bear, with the remainder of the stars in the Hyades being dogs that are holding the beast at bay.[52]

In Buddhism, legends hold that Gautama Buddha was born when the Full Moon was in Vaisakha, or Taurus.[53] Buddha’s birthday is celebrated with the Wesak Festival, or Vesākha, which occurs on the first or second Full Moon when the Sun is in Taurus.[54]

Astrology[edit]

As of 2008, the Sun appears in the constellation Taurus from May 13 to June 21.[55] In tropical astrology, the Sun is considered to be in the sign Taurus from April 20 to May 20.[56]

Space exploration[edit]

The space probe Pioneer 10 is moving in the direction of this constellation, though it will not be nearing any of the stars in this constellation for many thousands of years, by which time its batteries will be long dead.[57]

Solar eclipse of May 29, 1919[edit]

Several stars in Hyades cluster include Kappa Tauri were photographed during Solar eclipse of May 29, 1919 by the expedition of Arthur Eddington in Príncipe and others in Sobral, Brazil that confirmed Albert Einstein‘s prediction of the bending of light around the Sun from his general theory of relativity which he published in 1915.[58]

See also[edit]

IN THE NIGHT SKY

November 2019

Until November 23rd at around 15h, the Sun having passed through the constellation of Libra, enters Scorpius for just over a week, and enters the neighbouring constellation of Ophiuchus on the 30th at 10h.

The Moon

The Moon is at apogee, its furthest from the Earth, at 08h00 on the 7th, when its diameter is 30 minutes of arc. Perigee (nearest to the Earth) occurs on the 23rd at 07h00, diameter 32.5 minutes of arc. First Quarter at 10h24 occurs on the 4th in central Capricornus.

Full Moon is on the 12th at 13h35 on the Aries/Taurus border. It is a very high Full Moon as it crosses the meridian, around midnight.

Last Quarter is at 21h12 on the 19th, in the constellation of Leo, three degrees above Regulus.

The New Moon in November occurs on the 26th at 15h06 and is in the constellation of Scorpius, passing 2° north (above) the Sun.

You may be able to glimpse Earthshine on the night hemisphere of the waning crescent Moon from the 20th to the 25th, and on the waxing crescent during the first couple of days and the last four days of November.

The Planets

Mercury is at inferior conjunction with the Sun on November 11th at 15h. A transit of Mercury takes place, beginning at 12h36 and ending at 18h03. The transit is visible in its entirety from almost all of Antarctica, the whole of South America, the Caribbean Islands, the southeastern USA, eastern Canada and the southern tip of Greenland. Western Europe, the Middle East and Africa is the area where the Sun sets with the transit still in progress.

The rest of Canada and most of the USA and the Pacific Ocean is the area where the transit is in progress at sunrise until its end.

Unfortunately, most of Asia, the East Indies and Australia miss out on the transit because the Sun is below the horizon for the duration.

For your local area, add your time zone to the UT given for the start and finish of the transit if you are east of Greenwich; and if you are west of Greenwich, deduct your time zone from the times given. Refer to the diagram on the front page of these Sky Notes. Under no circumstances should you observe the Sun through any optical instrument. In order to see Mercury’s tiny disc, you will need to project the image of the Sun onto a sheet of paper, as per the instructions concerning solar observations on the front page.

After this, Mercury returns into the morning sky and reaches its greatest elongation west of the Sun (20°) on the 28th, when it may be seen some 10° above the SE horizon at around 07h at the end of the month. The fainter star-like object some 9° to the upper right of Mercury is the planet Mars.

During November, Venus slowly emerges from the vicinity of the Sun, when on the first of November it sets an hour after the Sun, increasing to two hours at the end of the month. Venus becomes the resplendent ‘Hesperus’ the ‘Evening Star’ of the ancients.

On the 24th Venus and Jupiter are in conjunction, with a separation of just over 1 degree (three moon-widths) in western Sagittarius. Venus is the brighter of the two and lies south of Jupiter; they will look spectacular in the field of view of a small telescope or binoculars at around 16h in the evening twilight. On the evening of the 28th, (16h) the thin waxing crescent Moon joins the planetary company in the twilight and lies between the two planets. All three are parallel with the SW horizon, with Jupiter 2.5° to the west of the Moon and Venus just less than 2° east of the Moon. The view will be enhanced by the presence of earthshine on the night side of the waxing crescent.

Mars, in Virgo, is a morning object shining at visual magnitude +1.7, not quite as bright as Spica (alpha Virginis), which lies 12° to the upper right of Mars. The colour contrast between the two is noticeable – Spica shining with a bluish white light and Mars being decidedly reddish. Throughout the month, Mars rises a couple of hours before the sun. (two hours at the start and three at the end). On the morning of the 24th the thin waning crescent Moon is in conjunction with Mars – the two lying 4° apart, with Mars below the Moon.

At the start of November Jupiter sets two hours after the Sun, reducing to one hour by the end of the month. It is therefore an early evening object visible low in the SW in the evening twilight. This is the last chance to observe the Galilean satellites before the Jovian system becomes engulfed by the glare of the Sun as the year comes to its end. Refer to the entry for Venus for phenomena involving Jupiter.

During November, Saturn sets about three hours after the Sun. It lies at a low altitude in Sagittarius, lying some 20° to the east of Jupiter and Venus, low in the SW sky at around 19h. The waxing crescent Moon may be seen approaching Saturn on the 1st, when at 18h the Moon is 7° to the lower right. The next night (2nd) the wider crescent may be seen 5° to the left of the ringed planet. Saturn currently shines at magnitude +1.2.

Uranus, is visible most of the night near the intersection of the borders between Aries/Cetus/Pisces.It is currently in Aries, some 10° south of Hamal(alpha Arietis). For an accurate position of Uranus go to the Remote Planets page accessible from the Menu above. Although the planet’s magnitude is +5.7, and is theoretically visible to the unaided eye, it is far better to locate it using binoculars or a small telescope. Through a telescope the planet presents a tiny greenish-blue disc 3.7 seconds of arc in diameter.

Neptune lies in the constellation of Aquarius with a visual magnitude of 7.9 and so requires binoculars or a telscope. With adequate magnification, it is possible to see this distant world as a tiny bluish grey disc. The angular diameter of the planet is just 2.3 seconds of arc. By the end of November, Neptune sets at astronomical midnight. Again, in order to locate Neptune, you are encouraged to visit the ‘Remote Planet’ page via the Menu.

There are two interesting meteor showers this month, the first of these is the Taurid meteor shower consisting of slow moving shooting stars associated with Encke’s comet and peaking overnight on the 5th/6thand again overnight on the 12th to the 13th. The Taurid shower is noted for producing bright slow moving events.

The Leonid shower peaks on the 18th at 23h, and so will be best seen in the hours before dawn on the 19th. Expect to see about 35 meteors an hour if conditions are favourable.. The next Leonid ‘storm’ is due to take place towards the end of the 2020’s. The parent body of this shower is comet Temple-Tuttle, which visits the earth about every 33 years.

Constellations visible in the south around midnight, mid-month, are as follows: Eridanus, and the Pleiades in Taurus. Perseus is at the zenith embedded in a rich star field – take a look through binoculars and see!

All times are GMT 1° is one finger width at arm’s length.

Regular Meetings

21st Hartshill Scout Group HQ, Mount Pleasant, Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire. ST5 1DP

Practical Workshop

Third Wednesday of the month (September – June)